Brutal Beauty: Scotland's Concrete Heritage Reconsidered

A new book by Simon Phipps turns his lens on Scotland’s often-maligned Brutalist architecture, revealing its stark grandeur and the social ideals that shaped it.

Brutalism has long been one of architecture’s most divisive styles — praised for honesty, derided for heaviness. In his latest book, Brutal Scotland (Duckworth Press, £30), artist and photographer Simon Phipps revisits the country’s concrete landmarks to ask whether they should be seen as relics of failure or as monuments to a lost era of civic ambition.

Phipps, known for his previous volumes Finding Brutalism, Brutal London, Brutal North and Concrete Poetry, has built a reputation for finding lyricism in poured concrete. His images combine precise geometry with quiet atmosphere, capturing the sculptural presence of buildings once dismissed as eyesores. With Brutal Scotland, he turns north to examine over 160 examples of post-war architecture, from megastructures and housing schemes to modest community centres and churches.

The book’s subjects span the nation — from the heavy forms of St Peter’s Seminary at Cardross, designed by Gillespie, Kidd & Coia between 1959 and 1966, to the University of Dundee’s tower blocks, Aberdeen’s concrete crescents, and lesser-known civic buildings scattered across smaller towns. Some have been demolished, others adapted, and a handful are now recognised as modernist landmarks.

For Phipps, documentation is preservation. Many of these structures are endangered; his photographs act as both record and argument for their continued relevance. "Brutalism was born of social optimism", he writes, "and sought to embody fairness and community in physical form". The Scottish examples — often shaped by harsh weather and pragmatic budgets — show a regional distinctiveness: tougher, more sculptural, and more responsive to landscape than their southern counterparts.

The book is also a reminder of Scotland’s post-war ambition. During the 1950s to 1970s, architects and planners were tasked with rehousing communities, rebuilding bomb-damaged cities and creating new spaces for education and worship. Concrete offered speed, flexibility and the visual language of modernity. Many of the results, though now weathered and polarising, reflected an optimism about design’s power to improve life.

Today, as city councils debate redevelopment and demolition, Brutal Scotland captures a moment of reassessment. Phipps’s lens is sympathetic but unsentimental. The photographs record streaked façades, encroaching vegetation and the play of shadow across angular planes. Yet there is dignity here — and a sense that, stripped of prejudice, these buildings reveal a sculptural poetry.

Notably, Phipps’s Scottish survey joins a broader cultural revival around mid-century modernism. In recent years, local campaigns have sought to protect structures such as the Category A-listed St Peter’s Seminary and Cumbernauld Town Centre, while exhibitions and archives have begun reframing concrete architecture as heritage rather than embarrassment. Brutal Scotland contributes to that shift, offering a visual and historical inventory at a time when many of these buildings face uncertain futures.

Phipps’s previous books have helped to transform perceptions of Brutalism, elevating it from architectural footnote to cultural fascination. The Scottish edition continues that mission, with design by the publisher Duckworth that foregrounds photography over commentary. The result is part visual atlas, part act of advocacy — a portrait of a country seen through the lens of its most misunderstood material.

For readers, the appeal lies in both rediscovery and reflection. Buildings once passed without notice emerge as artefacts of ambition; concrete becomes a carrier of social history. Whether loved or loathed, they are undeniably part of Scotland’s modern identity.

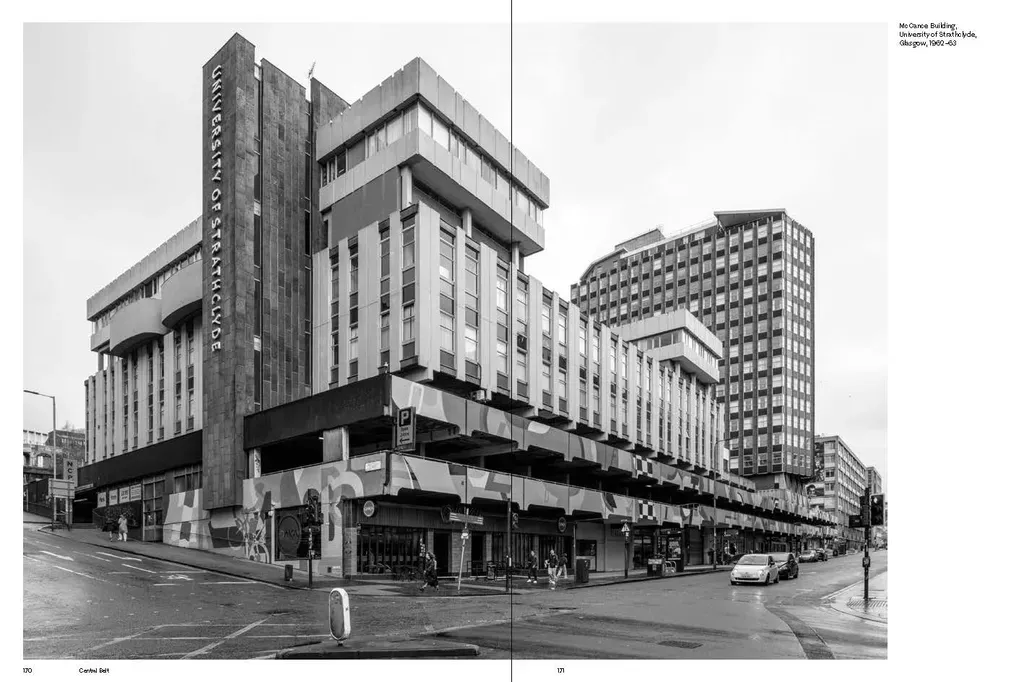

Clockwise from top left-hand corner: McCance Building, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, 1962–63, Covell Matthews & Partners; Clydesdale Bank (now Virgin Money), Kilmarnock, 1975-76, Hay, Steel & Partners; Gordon Aikman Lecture Theatre (previously George Square Theatre), University of Edinburgh, 1965–70, Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners (RMJM); Woodside, Glasgow, 1970-74, Boswell, Mitchell & Johnston. Images: Simon Phipps / Duckworth Books.

Brutal Scotland is available now from Duckworth Books (£30).